By carefully observing recurrent diachronic patterns, historical phonologists are able to make out generalizations and thus arrive at a better understanding of sound change. In tone languages, however, much work still needs to be done outside the segmental realm of consonants and vowels. Numerous uncertainties lie ahead: How do pitch contours change in tonal categories? Are such changes linguistically motivated — that is, not by factors other than language and its workings? Joe Pittayaporn’s study aims to bring to light prevailing biases in human speech responsible for the trajectory of sound change as witnessed in the case of Bangkok Thai tones during the past century.

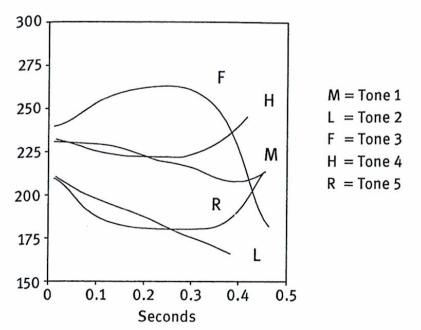

In Thai, there are five lexical tones which contrast in terms of pitch height and contour, as illustrated in Figure 1. Ample instrumentally documented descriptions of Thai tones produced in the past century allows for comparison of the phonetic characteristics of the tones.

Figure 1 Thai tones in the early 21st century (from Zsiga, 2007: 399)

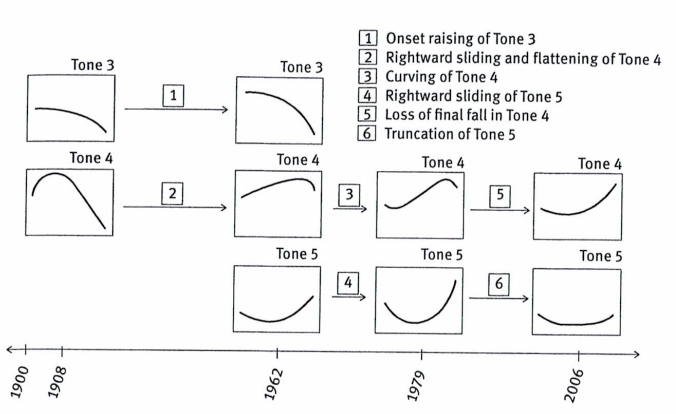

Figure 2 reveals gradual contour changes of Thai tones, especially for Tones 3, 4, and 5. Data from four points in time (Bradley, 1908; Abramson, 1962, 1979; Zsiga, 2007) shows that during the early 20th century the onset of Tone 3 rose up so that it became a high falling instead of mid falling tone. More interestingly, Tone 5 went through a rightward shift in rise time throughout the latter half of the century, truncating the contour so that its peak now narrowly touches the middle pitch range. Perhaps the most intriguing example, Tone 4 seems o have undergone three different stages: a rightward shift in rise time, a flattening, an initial curving, and an omission of the final fall. Interestingly, Tones 1 and 2 have stayed quite stable.

Figure 2 Timeline of tonal contour changes

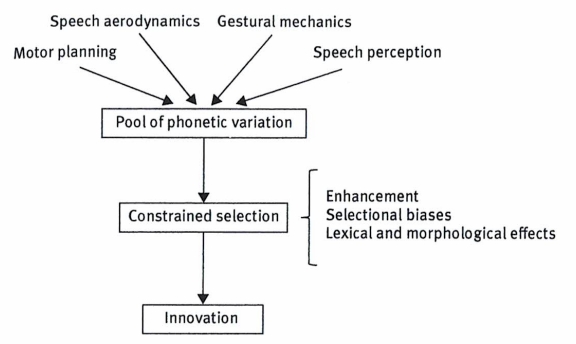

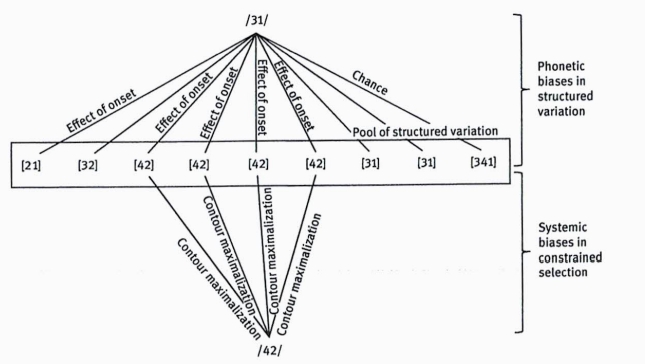

In this study, Pittayaporn moves beyond a descriptive account of the tonal changes by explaining them through the lens of a phonetically-based approach to sound change and acknowledging the interplay between phonetic and systemic biases. In brief, phonetic biases (such as motor planning and gestural patterning in the previous nasal vowel example) give rise to a pool of phonetic variants. These variations undergo a selection process where systemic biases influence which variant wins out and gets adopted, disseminated, and eventually established within the speech community. The entire process of phonologization is summed up in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Elements of sound change (based on Garrett & Johnson, 2013)

Turning first to phonetic biases, we see three main phonetic factors at play: peak delay, contour reduction, and syllable onset effects, as follows.

- Peak delay (e.g. rightward sliding and loss of final fall of Tone 4): Sharp rises take longer to terminate, shifting the pitch peak rightwards

- Contour reduction (e.g. flattening of Tone 4): Reduced, less exaggerated contours in short vowels and unstressed syllables

- Effects of syllable onset (e.g. onset raising of Tone 3): Beginning (onset) of the pitch affected by preceding consonant

The variants generated by these diverse phonetic biases are then selected under the a set of systemic constraints or biases. Here, we also observe three main systemic biases at hand:

- Contour maximization (e.g. keeps raised onset variant of Tone 3) favors dynamic tones with more dramatic contours, allowing greater contrasts

- Contour accentuation (e.g. keeps curved variant of Tone 4) introduces a new, enhancing feature to further distinguish the tones

- Avoidance of similar tones (e.g. rightward sliding and flattening of Tone 4 in relation to rightward sliding and subsequent truncation of Tone 5, augmenting perceptual distance) maximizes distinction between tones

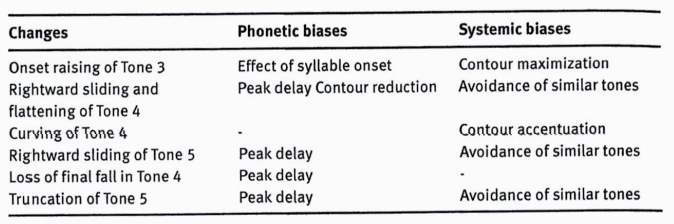

Most importantly, the tonal contour in Bangkok Thai has gone through two separate yet related processes interacting in a linear order, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 Summary of biases motivating contour changes in Thai

Most of such changes are accounted for by both phonetic and systemic biases. As an example, Figure 4 illustrates phonologization of Tone 3, involving a possible effect of syllable onset and contour maximization. Nevertheless, some trajectories of change are unclear as to whether they entail both types of biases. For example, the loss of final fall in Tone 4 seems to have been affected solely by peak delay, a phonetic bias. The constrained selection was possibly driven by frequency instead of systemic biases.

Figure 4 Phonologization of the high falling contour of Tone 3

In essence, Pittayaporn’s work sees the tonal contour changes in Bangkok Thai as motivated by phonetic and systemic biases in the phonologization process of speech, uniting changes in lexical tones with those at the segmental level which are better understood among the literature of historical phonology.

Ratanon Jiamsundutsadee

References

Abramson, A. S. (1962). The vowels and tones in Standard Thai: Acoustical measurements and experiments. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Research Center in Anthropology, Folklore, and Linguistics.

Abramson, A. S. (1979). The coarticulation of tones: An acoustic study of Thai. In T. L-Thongkum, P. Kullavanijaya, V. Panupong, & M.R. K. Tingsabadh (Eds.), Studies in Tai and Mon-Khmer phonetics and phonology in honour of Eugenie J.A. Henderson (vol. 1–9). Bangkok, Thailand: Chulalongkorn University Press.

Bradley, C. B. (1911). Graphic analysis of the tone-accents in the Siamese language. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 31(3), 282–289.

Garrett, A. & Keith, J. (2013). Phonetic bias in sound change. In A. C. L. Yu (ed.), Origins of sound change: Approaches to phonologization, 51–97. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Zsiga, E. (2007). Modeling diachronic change in the Thai tonal space. Paper presented at the 31st Penn Linguistics Colloquium, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.